Greybox Your Game

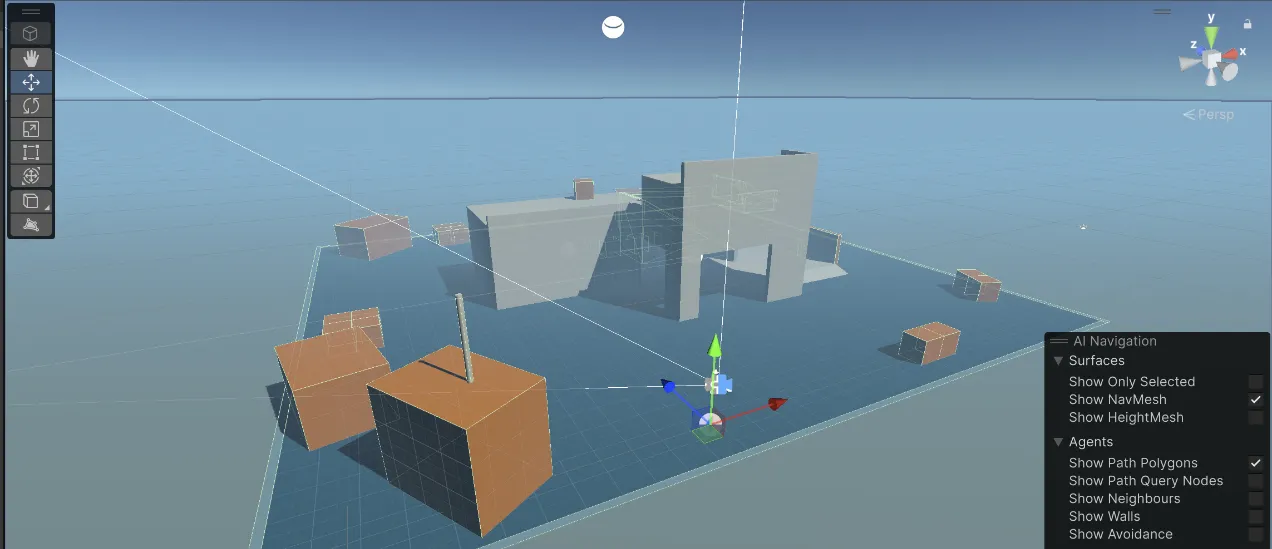

The purpose of greybox prototyping is to get something payable in front of a playtester without having to produce any new assets. Instead, basic shapes like cubes and spheres are used as a stand-in for models that will be produced later. This approach is popular for both developing mechanics and for level design.

Just about every major development studio does some form of greybox prototyping. We’ve talked about paper prototypes, and wireframe prototypes, which are mostly low tech options. But some games have features like physics and timing that significantly impact your game, and are harder to accurately test with low tech prototypes. No matter what type of game it is, eventually you’ll want to prototype using the tools that you’ll be developing with. This is where greybox prototyping comes in. Building your prototypes using the engine you’re making your full game with allows you to playtest immediately, and integrate newly tested features quickly. Example of a greybox prototype from Unity’s tutorials

Like all prototypes, the greybox prototype aims to give you insight about your game ideas so that you can make an informed decision before committing time and energy to implementing a feature. Greybox prototyping is versatile. It can be used for all sorts of testing, like UI usability, or cultivating game feel. The two most popular uses though, are developing mechanics and designing levels.

Greybox Prototyping for Developing Mechanics

Using greybox prototypes to design game mechanics means focusing exclusively on the mechanic while limiting the creation of art assets, sound, and other elements of your game that don’t directly impact the mechanic you’re designing. Of course, if you’re designing a new mechanic that relies heavily on a physics engine, you’ll probably want to develop something inside of your game engine to really get the full effect, but try to keep your scope as limited as possible.

Mario 64 famously spent months of development as a greybox prototype, with nothing but Mario moving around in a test room. At the time, no one had successfully translated platformers from 2D to 3D setting, and Shigeru Miyamoto believed that the key to this translation was to get the player movement perfect. During these months no other assets for the game were created. While testing, Miyamoto requested that his team create numerous animations in an attempt to make Mario’s movement fluid. Miyamoto’s reasoning for this was:

-

"... as players got good at the controls, they’d want to try out more and more button combinations, and if there was nothing past the basics it would be disappointing for them. So we created movements for all button combinations—of course, that means a few useless ones got left in too. (laughs)"

- Shigeru Miyamoto

Miyamoto continued to greybox test until he felt that simply moving Mario in 3D felt fun. At the end of development Mario had a whopping 209 unique animations. Miyamoto’s hard work paid off and Mario 64 became a prime example of how to do 3D platforming right.

Level Design

Greybox prototyping is great for producing and iterating over levels quickly. Rather than creating new assets for a level, you’re saving time and money by creating the same geometry or general shape you want and testing it early before creating the final assets. This can be helpful for getting things like platform placement and enemy AI correct before implementing them in the final game with final assets.

Thanks to channels like Beta 64 and websites like The Cutting Room Floor>, we now have unprecedented access to unused assets that didn’t make it into their final games, but were still stored in memory. Mostly this includes tools used for development and debugging. In many cases these include test greybox rooms and levels themselves.

In Kirby’s Adventure, thanks to debug tools, we can see several rooms that use temporary assets. In many cases these levels correspond to finalized versions that were included in the completed game.

Emergent Complexity while Greybox Prototyping

Greybox prototypes can often help you find emergent complexities in your game while testing. The more rules and mechanics you add, the more interactions exist. Many interactions will be purposefully placed, but some might be a surprise, and not what you planned. This is also known as emergent complexity, and it’s not always a bad thing!

If you play a First Person Shooter long enough you’ll come across a trick that players use to jump much higher than normal by using the knock back from an explosion. It’s called a “Rocket Jump”. Though they are pretty standard now, they were not intentionally programmed at the time. Both rules (knock-back from an explosion, and how much damage a player could take) were developed individually, and were later discovered and used together by players.

Alien: Isolation started as an internal prototype. The developers of Alien: Isolation found that playing a quick game of hide and seek with one player controlling a human, and another controlling the alien, was not only fun, it really captured the feeling of being hunted. If it wasn’t for the success of the initial prototype, this game may have never been green-lit.

Alien: Isolation

-

“…that little tech demo went a bit viral within Sega, and suddenly it seemed like this pipe dream of making a game based on the original Alien [film] started to get some momentum.”

- Alistair Hope

Whether it’s planned or not, new interactions can completely change the way you think of your game. Taking the time to test mechanics and interactions in a greybox prototype can lead to finding untapped potential, or at least a few unforeseen bugs to work out.

If you’re looking to make a faster or less technical prototype, try one of these other methods.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack