How Much Art Should a Game Prototype Have?

It can be hard to know when your prototype is polished enough for other people to play.

When you’re first starting on a new game, excited and trying to get all of your ideas down quickly, it can be hard to know when your prototype is polished enough for other people to play. Whether your game is digital, physical cards, or something in between, game art is extremely important to both the theming and usability. If you give a playtester a bunch of gray boxes with numbers you might not get the feedback you’re looking for, but spend too much time making it beautiful and you could end up with a lot of sunk costs. So how do you decide when your prototype has enough art? Here are two common approaches-

Scrappy, Ugly, and Fast Prototypes

When you’re starting on something new, getting something done is the most important thing. If you spend too long ideating and writing out ideas you can very easily lose momentum and end up dropping the project. The faster you can get something, anything, into a playable state the better chance you have that the project will continue.

Having something made quickly also gives you the ability to make quick changes based on early feedback. You don’t need to make brand new art or order new cards if it turns out a mechanic isn’t working, you can just cross it out with a pencil or delete it. It also means you won’t feel horrible about the time you spent on that mechanic, which can cloud your decision making.

Depending on who you’re making the prototype for, something beautiful might be a hindrance. A publisher looking to buy your concept can get nervous if the game is too polished, assuming you will fight them about any art changes. Or if you’re planning on working with an artist or UI/UX designer later, you might be influencing them to go in a direction they might not have originally.

The original box art for Décorum, and the final box art from the publisher.

Polished, Pretty, and Clean Prototypes

Getting feedback early is important, but if players don’t know how to play you won’t get the feedback you want. Feedback on usability is always helpful, but when you’re just trying to gauge if the main mechanics are fun, it can get in the way and cost a lot of time. Making something clear and easy to use will always result in better playtester notes.

Theming for a game isn’t always something that is secondary to the mechanics, in fact in most cases they should be going hand in hand. If you put off adding art and polish that suits your themes too long, you can miss out on feedback that would allow you to pair the two much better. This is especially true if you’re following top-down design principles. In many cases, the theming actually affects how people feel about the mechanics, even if they couldn’t articulate why, so you might end up needing to do a lot of rebalancing after the art has been added.

Having a playable game early is important, but if you don’t feel any sense of pride over what you’ve made it can really slow you down. Making version after version of gray boxes and scribbled cards can make you feel like all your work has been for nothing and you’re losing momentum, no matter how much work you’ve actually put in! This is true for your playtesters as well, if they see that the game looks “the same” you’re likely to get some of the same feedback, even if it shouldn’t be relevant anymore.

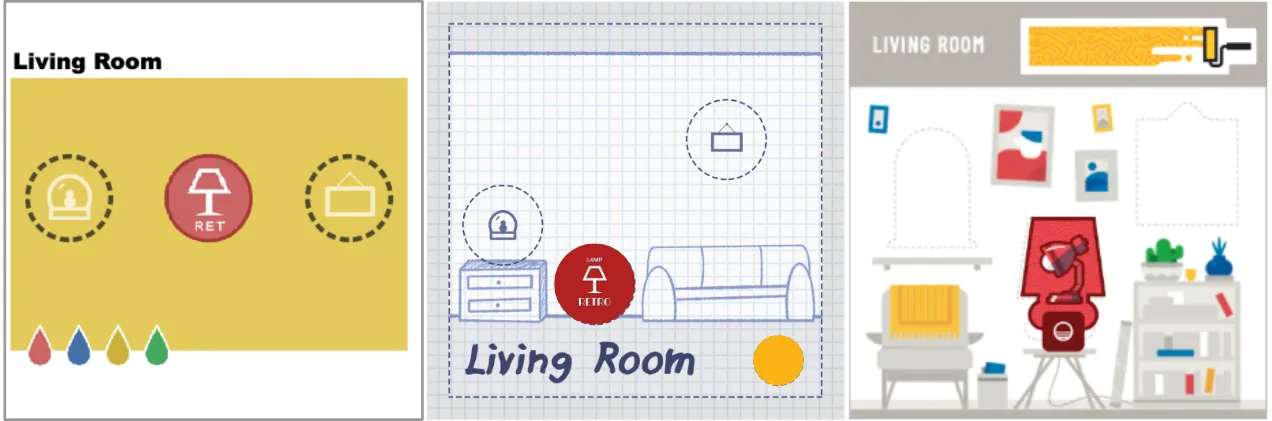

Décorum at different stages of development. Starting with only enough art to play, then adding more art and a blueprint theme, then the final art from the publisher.

So How Do You Choose?

When you’re starting your prototype, think about who you’re making it for. Do you want your friends to test it? A potential publisher? A client? Know who your audience is, and what type of feedback they’re likely to give. Someone who doesn’t know much about games is going to need more polish than someone who plays games everyday. They aren’t going to understand the shorthand you’re relying on, where a regular tester might be able to pick it up without much to go off of at all.

Think about what kind of developer you are, without judgment. If you’re not a great artist yourself, it would probably take a long time to get nice art into your prototype. Time you might not want to spend right at the start, especially if it puts you closer to dropping the project. On the other hand if you know you’ll get discouraged if your game looks ugly to begin with, maybe it’s worth it to you to spend that time and get something you’re excited about. Especially if you tend to design with art, tone, and theme in mind!

At the end of the day, it doesn’t have to be so black and white. There’s no rule saying you can’t switch between working on mechanics and polish whenever you feel like it; and there are lots of fast ways to add polish before you get to your final draft. Personally, I prioritize making my games user friendly so they test well early on, but don’t spend much more time on art until I’m happy with gameplay. As long as you stay flexible, and really keep your own personal goals in mind, you can find the best workflow for your game.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack