Core Game Mechanics

The core gameplay mechanism, or "core mechanic" can be defined as the actions that a player repeats most often while striving to achieve the game's overall goal. - Game Design Workshop

It’s easy to be distracted by parts of your game that aren’t central to the core experience. Sometimes it’s hard to know which parts are important, and which aren’t. Clearly identifying your game’s core game mechanics can help you focus your design, and make a much more successful game overall.

Whether you have an idea for a great game, or need to fight feature creep in a current project, these exercises will help you identify your game’s core game mechanics, and keep you focused.

Write an Essence Statement

To identify your game’s core mechanic, begin by writing a short (one to two sentences) description of what the player does when they play your game. This description will be your game’s essence statement. Not only will the game’s essence statement help you to communicate what your game is about, it will also remind you (and your team) why you’re making the game in the first place.

A good essence statement conveys the player’s goal, the actions a player can take, and their role in the game in 1 or 2 sentences. For example, DOOM (2016)’s description reads:

From this description we know exactly what to expect when we pick up the game.

- We know the goal: "beat[ing] back Hell’s raging demon hordes"

- We know the actions: "slash, stomp, crush, and blow apart demons" (Player actions are usually in the form of verbs.)

- We know the role: "you" (This implies that it will be a first person perspective.)

On top of the roles, goals, and actions in the description we also learn a bit about other mechanics that add to the player’s experience.

“There is no taking cover or stopping to regenerate health” highlights two game mechanics that set DOOM apart from other modern shooters. Unlike Call of Duty or Halo, players are encouraged to play aggressively. By eliminating cover, players are forced to act and think quickly. At the same time, the player receives a lot of health by performing melee attacks. Bringing the focus back to the advanced melee system and player actions of “knock-down, slash, stomp, crush”.

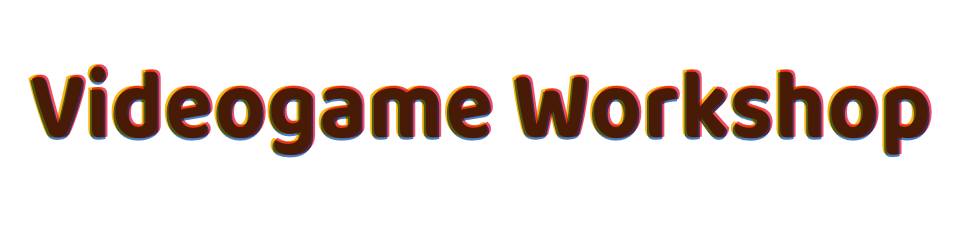

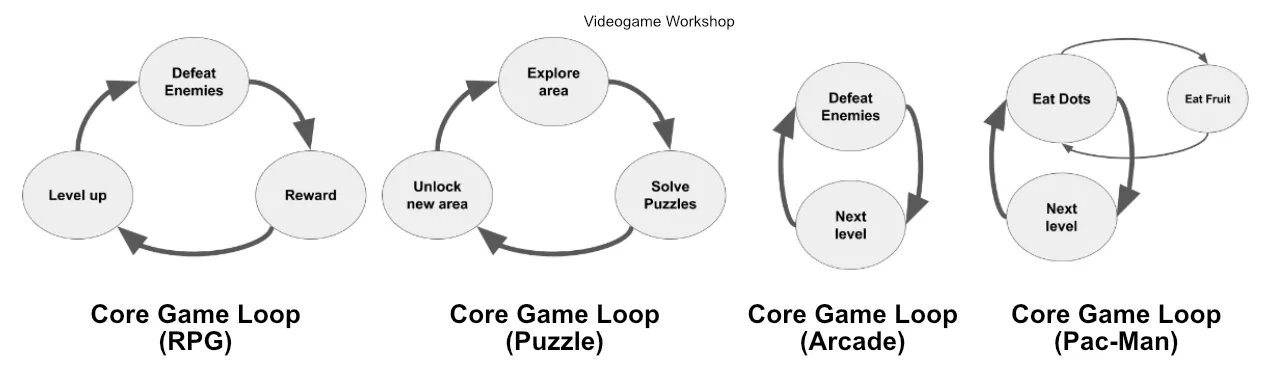

Create a Core Game Loop Diagram

Another way to determine what the core mechanics of your game are is to create a core game loop diagram to visualize the core gameplay. This diagram shows the series of actions players take in order to play the game. In other words, what is the player doing over and over again?

Diagraming your core game loop is a good way to focus/edit your game and can be shared as a blueprint with your team. Your core game loop should also support your game’s essence statement.

RPGS, as a generic example, can be described as a loop that contains the actions: Defeat enemies, Get Reward, Level up, Repeat.

Generally, all of your game’s core mechanics should be in service of the core game loop. If one of your game’s mechanics doesn’t support your game’s core game loop or your essence statement, you might consider eliminating it.

Examples of common core game loops and one specific example using the game Pac-Man. Although the core game loop of your game won’t look exactly like the examples, they’ll probably look very similar.

You’ll notice that the diagram for Pac-Man is essentially the arcade game loop with an additional sub-loop (Eat Dots, Eat Fruit, Repeat). You’ll also notice that there is no way to get from the Eat Fruit bubble to the Next Level bubble. This is because in the game, Pac-Man eating fruit is not required to progress, but eating dots is. In fact, you could probably remove the Eat Fruit bubble completely and still have the essence of Pac-Man. This tells us that although Eating Fruit increases your score and feels good (it provides an added challenge) it isn’t a core game mechanic and could be removed without drastically changing the game (it does change the game feel, but more on that in another post).

Your core game loop may also have sub-loops. Going back to our generic RPG game loop, you could argue that not every fight gives you enough of a reward to level up. Most RPGs include some sort of grinding where players must have several enemy encounters before they level up. Similarly, some adventure games may follow the generic Puzzle diagram, but may require the player to solve multiple puzzles before moving to the next area.

More complicated example diagrams.

Unlike the diagram for Pac-Man, where Eating Fruit was optional, none of the bubbles in these diagrams can be removed without breaking the loop. Indicating that each bubble is an important part of the game.

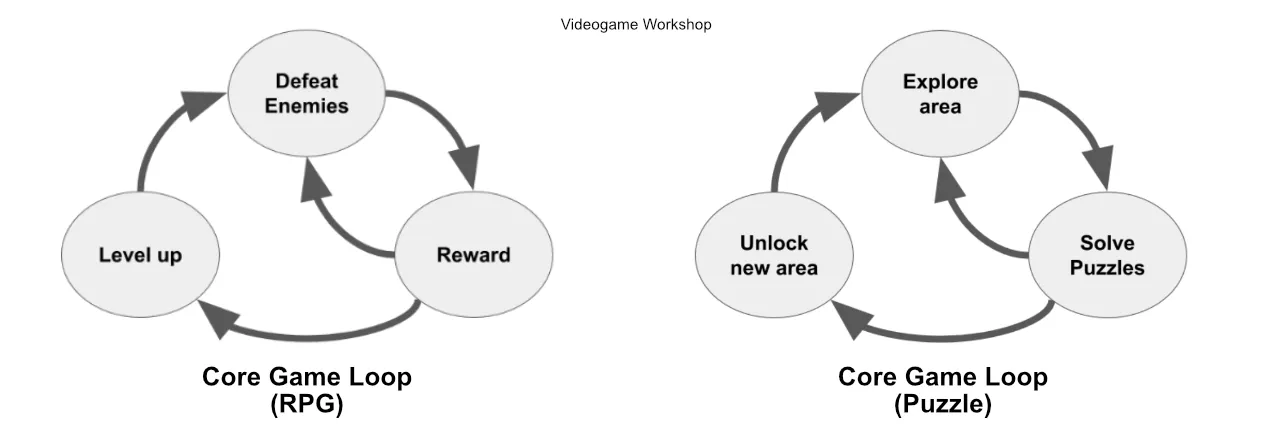

Create a Noun/Verb Diagram

Another diagram you can make to find your core mechanics is the noun/verb diagram. This technique tries to visualize what a player can do by showing the relationships between the important objects in your game (nouns) and the actions a player can take (verbs).

First, we need to identify all the major objects in our game. For Pac-Man, this includes the Player, the Ghosts, the Dots, the Fruit, and some non-obvious things like the Score. Because this diagram is focused on player interaction, these nouns generally do not include things that only exist in your code, such as a game state controller, UI controller, etc.

Next, draw lines between any two nouns and use a word or two to describe how they interact (verbs). For example Ghosts -Chase- Player and Player -Eats- Dots.

Diagram of example.

You’ll notice that in this diagram the player has the most arrows pointing to/away from it. This makes sense since you generally want your game to revolve around the player and their actions. If you find that some other object has more actions associated with it, consider why that might be the case and see if you can’t shift the focus back to the player.

Kill Your Darlings

If you finished the exercises above you might notice that some elements of your game didn’t make the cut. That’s ok, in fact, editing your game to focus on the core mechanics is a good thing. If you found the previous exercises difficult, or struggled to fit all your mechanics into 1-2 sentences, it might be time to rethink what mechanics are core to your game. In order to address this, go back to your essence statement and think about the core experience you want to present to your players. Ask yourself if all of the mechanics you’ve identified above reinforce, or distract, from that experience and cut the ones that don’t fit.

It’s generally better to get one core mechanic right than to have several that aren’t very fleshed out. If you’ve ever played a game where it feels like a certain part was added as an after thought, you know what I mean. Another way to think about this is, unless the game was focused on crafting, a crafting system would be really out of place in a Mario game. In fact, having a crafting system might really detract from the platforming mechanics that are at the core of most Mario games. So don’t be afraid to cut out the unnecessary elements. This part is difficult, and it’s a good idea to keep a notebook handy to write down any of the ideas you like, but don’t exactly fit into this game. Who knows, maybe they’ll be the core of another game.

Editing is hard, and if you’re having a difficult time with it just know you’re not alone. The great YouTube series Extra Credits has an excellent video on editing that I highly recommend watching if you’re having problems with this part of the design process.

Revisit and Reimagine Mechanics

If you feel that your game is a bit lean, try finding ways to iterate on your core mechanic rather than introducing new mechanics. Nintendo does a great job of keeping their games focused on a few core mechanics, which they then use multiple times in new and interesting ways.

- Shigeru Miyamoto

A big part of translating Mario from 2D to 3D in Mario 64 was making sure that Mario jumped around in fun and interesting ways simply because jumping was the core mechanic. As Miyamoto stated in an interview for the Mario 64 strategy guide:

- Shigeru Miyamoto

For your game, this might mean revisiting a mechanic that you haven’t fully explored and seeing new ways it can be used.

Hopefully these exercises will help you better understand your game’s core game loop and the core mechanics that support it. Whether you use them to communicate ideas with your development team, or fight against feature creep, the time you spend focusing your design will be well worth it.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack