Design Diary: Operation Investigation

Our Design Diary series showcases the behind the scene development of our previous client games. Operation Investigation was made for Twin Cities PBS and released on the Apple App Store and Google Play Store alongside the launch of Hero Elementary in 2020. Operation Investigation won several design awards including, a Serious Play silver award, two Telly awards, a Kidscreen award, and a Gee award.

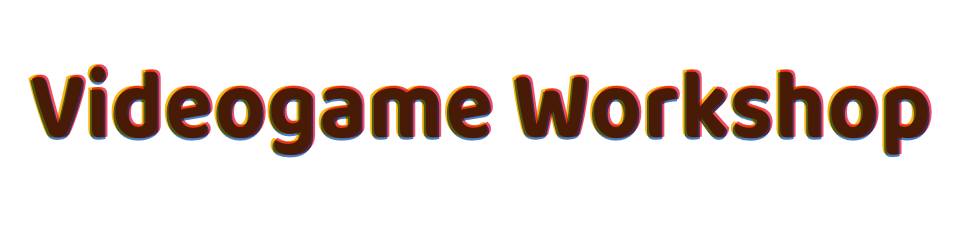

Operation Investigation is a deductive reasoning game where 2-5 players investigate animal traits to find the best match for a target animal. Players take turns making observations and collecting data about animals. Then, they discuss and compare their findings, deciding as a group to continue collecting data, or submit an answer. Players are following the scientific method, and practicing STEM skills in an age appropriate, relatable way.

Our back end has a bank of animal data that the game pulls from to create countless different puzzles for players to solve. With at least one entry for every variation of Weight, Habitat, Diet, Speed, Texture and Sleep Schedule, the animals’ players see each round are constantly changing.

This game was very different from the other games we had made for Hero Elementary. Not only was it multiplayer, but it was aimed at families as a whole rather than a specific age group. This changed a lot about how we approached the design, and introduced some unique challenges.

While studies show that family engagement in children’s education has long lasting positive impacts, creating that engagement can be difficult, especially around a videogame. In our early testing, we found that many parents didn’t understand that they were supposed to be playing the game alongside their children. Even when we explained, many of them were hesitant or confused. We also noticed that kids who were confident would often physically take the tablet away from other players, whether that’s their parents or younger siblings, and essentially try to play the game themselves under the guise of helping the other players.

To combat these challenges we introduced a few new mechanics. First, we asked each player to select a skill at the start of gameplay. The skill they choose is connected to a character and a specific animal trait they can test. For example, Sara Snap tests the weight of the animal. This made it so each player could only test for a single trait, which isn’t enough to figure out the correct answer on their own. It incentivized more communication between players, and made it very clear who’s turn it was so passing the tablet would be easier.

We also added dedicated screens prompting review and discussion at the end of each round. Parents often felt most comfortable playing when they could act as a trusted advisor or expert, but didn’t know when to jump in. The review screen gave them that invitation, while also prompting players to use the comparison skill we’re teaching.

The final screen in a round is the option to make an informed guess, or keep testing for more data. This was very helpful not only for impatient players, but because it gave all the decisions weight. They didn’t just keep testing until they got the right answer, everyone had to discuss and agree, because they could be wrong!

Once the base game was complete, we wanted to find a way to continue expanding the game’s content. Initially we had planned thematic updates that corresponded with holidays, seasons, or new episodes of Hero Elementary. However, we also wanted a solution that would allow for more organic growth of the game’s content over time. Thankfully, we had a generic structure that could support all of these.

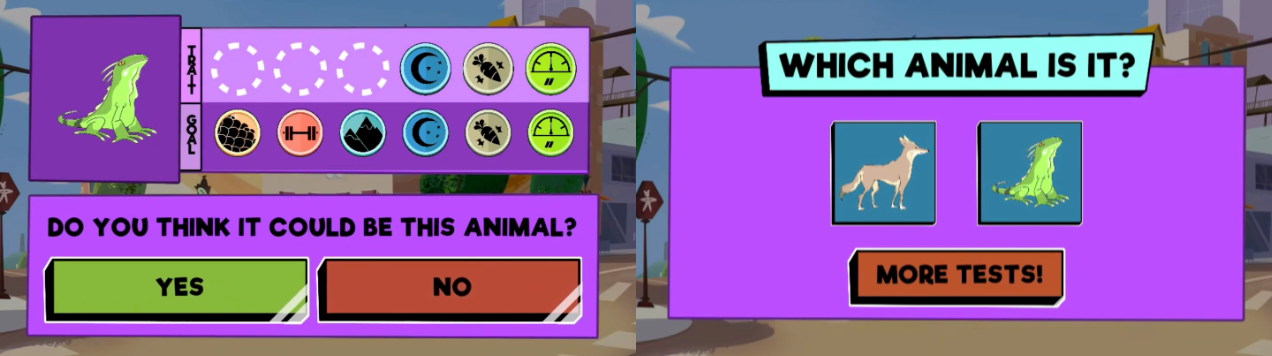

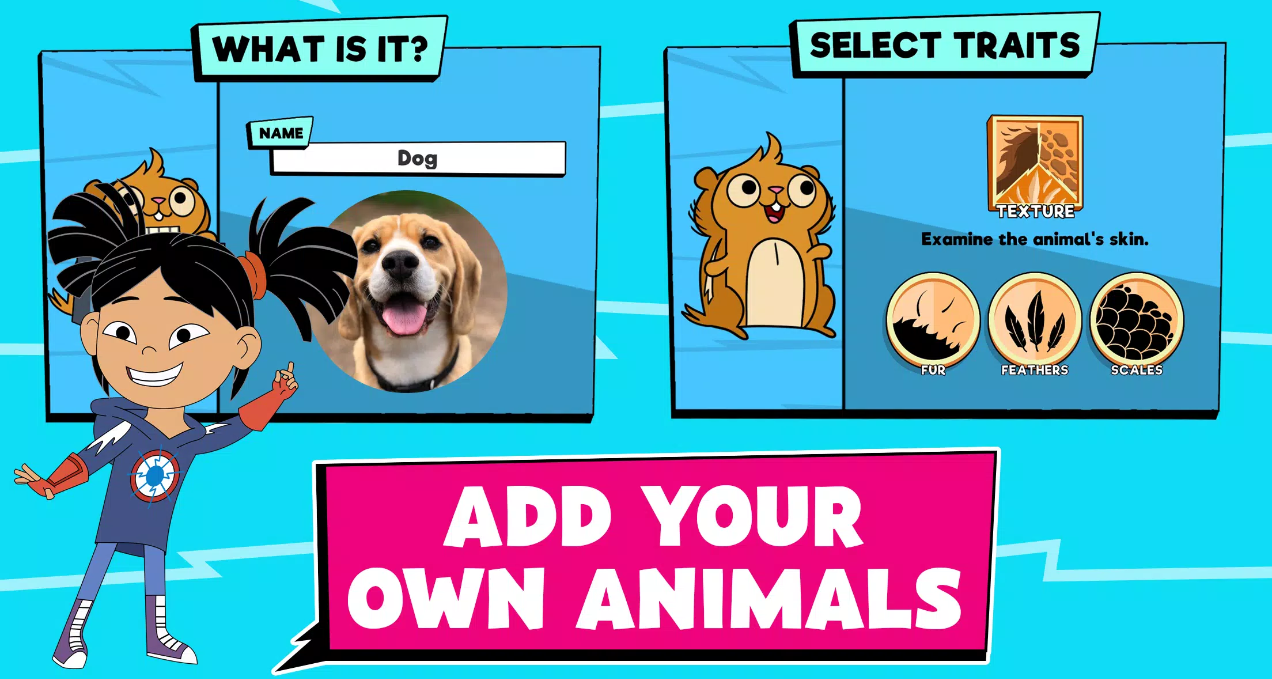

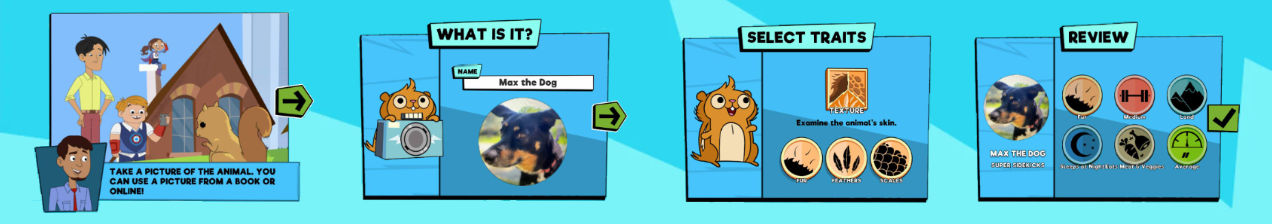

To solve this problem, we created a system that allowed players to contribute their own animal data to expand the game’s content. A new user-generated “Make” section. Players are asked to take a picture of an animal using their device camera, name the animal, and then classify it using the six classification measures used in the main game. The animal is then added to the bank and would show up as a potential match in future rounds of the game. It might even end up being the target animal!

Players would often use the Make feature to add their pet, imaginary animals, and even their younger siblings to the game. Which we encouraged! While none of these additions would usually be added to this kind of list, players were still using the same classification skills and often had thought out reasoning when asked why each trait was added. Adding an animal that didn’t quite fit was causing them to adjust their mental model of what each trait was and how it could present in the world around them. This also had the added benefit of increasing our average play time. Players would create a new animal and be so excited at the possibility of seeing it in the game that they’d go back to the Play section after using the Make section.

Adding their own animals to the game increased player engagement by giving them a sense of ownership and contribution to the game world. It also allowed players to explore and question the traits we used for classification. Many of the traits like Speed and Weight are relative, causing the player to stop, reflect, and compare previous answers given. We wanted these measures to be flexible enough to accommodate for a comparison, and broad enough that a child in our age range would have no trouble describing animals using that vocabulary. For example a player can think that their dog is heavy, but they know that an elephant is labeled heavy, and their dog isn’t as heavy as an elephant so maybe they’ll label it medium.

While the app was available, it held an average of 4.5 stars on both the Apple App Store and Google Play Store with many players commenting positively about the ability to add their own animals to the game. Common Sense Media praised the feature for encouraging creativity and exploration giving the game a “Recommended” with 4 Stars. Read the review here.

Awards:

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack