Design Diary: Push Pull Puzzles

Our Design Diary series showcases the behind the scene development of our previous client games. Push Pull Puzzles was made for PBS Kids and released with the launch of Hero Elementary in 2020.

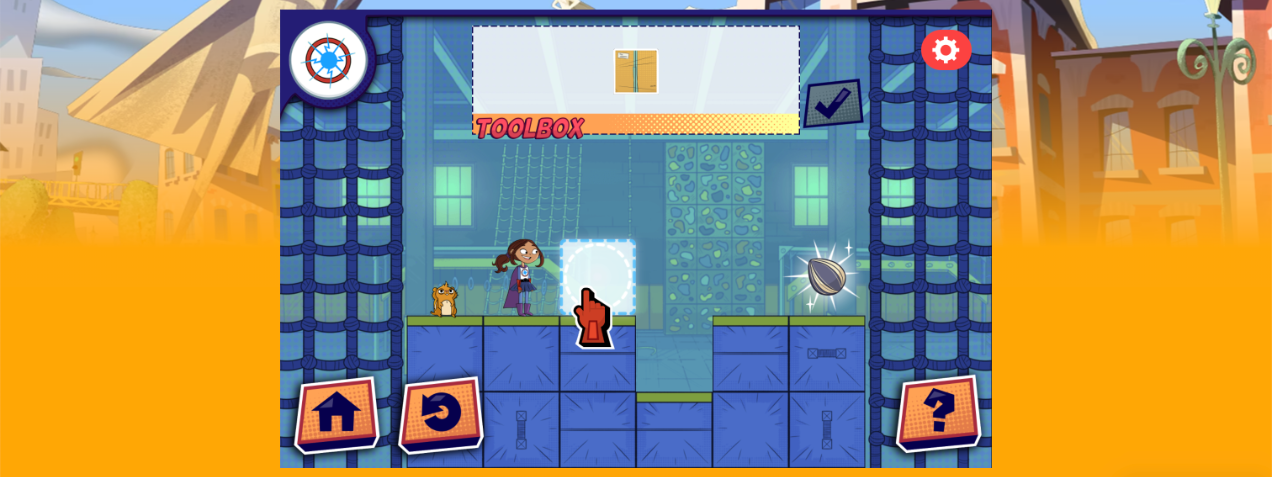

In Push Pull Puzzles players solve simple physics puzzles to clear a path for Fur Blur to get to her snack. Players place objects and manipulate them on a grid in order to create steps, push buttons, activate levers, and more. Learners observe, make a hypothesis, and test their theories.

When we first started development on Push Pull Puzzles we only had a vague idea of what our TV world and characters were going to be like. As development of the game went forward so did the TV show and we had to be very flexible to make sure we didn’t contradict a show that hadn’t been written yet. One thing that did remain consistent, however, was our learning objectives. Our education experts used the Next Generation Science Standards to create subject areas and learning objectives for Hero Elementary. Then, we pitched game concepts to cover those subject areas. Push Pull Puzzles teaches learners about the concept of force, and how factors like ramps, ledges, the shape of the object being pushed, and weight can impact force in motion. We wanted our main mechanics to be centered around the verbs pushing and pulling; we thought this was a great opportunity to show off some super hero action.

We talked with kids in our age range, asking them to draw examples of things they push and pull.

We knew we wanted to be able to depict differing strengths of pushes, and pulls to show how it affects the distance the object will travel, but we needed an in-world reason to justify it. Thankfully we had a superhero with super strength that we could highlight which allowed us to compare small pushes with big pushes when contrasting with another character for regular pushes and pulls. This was our first real combination of science and superpower. We were able to use the fun and exciting story elements to draw kids’ attention to the science behind it, and it was a huge success.

Sara Snap, one of the main characters in Hero Elementary, has super strength.

During development key parts of the characters were reordered and changed. Names changed, character designs changed, and even the show’s name changed from Hero School to Hero Elementary. Thankfully, because we used a bottom up design approach, we were able to pivot rather easily since we still had a hero with super strength to work with. After some asset swapping the game was once again in-line with the show (but never ask us why Lucita can’t just fly over the level. Let’s say it’s practice.).

Lucita Sky’s character design changes during game development.

The first iteration of the game had 44 puzzles broken up into four “worlds”, each increasing difficulty level and introducing new mechanics like switches and levers that made you think about the sequences of your pushes and pulls. Each world contained 10 levels and each level had to be completed to move forward. Finally, each world also had an optional boss level. The boss level could only be unlocked if the player was able to beat all the levels in its world using only one turn. Levels could be replayed to allow players to unlock boss levels later.

We designed 80 levels working in a Google Slides template based on our in-game grid system.

As we got closer to our show launch, PBS decided they wanted this game to be one of the four games from our property they would feature on the PBS Games App and website. However, they requested a few changes to the game in order to better serve their slightly different audience.

PBS liked our structure, but asked us to reduce the number of levels to 22. They felt that based on the amount of time their players spent per game this would be enough content to keep them engaged without overwhelming them with choice. They also asked us to make the 20 base levels available to play in any order, only allowing the boss levels to be locked. Their concern was that players who had previously played the game on another device would be frustrated that they needed to start over from level 1, and wanted them to be able to jump directly to any level so they could continue playing.

The new PBS approved level select system with all levels unlocked.

These changes brought up a few concerns for us. We worried kids who were playing the game for the first time would miss the tutorial, and play levels out of order which could add additional and unintended difficulty. We decided to compromise with PBS by starting the player inside level 1 when they first open the game, but give them access to a home button immediately that they can use to go to level select. Most new players stayed in level 1, and then used the “next level” button to continue, keeping the order intact, while still allowing experienced players to jump between levels as they wished.

World 1 level 1 contains important tutorial elements, like how to place objects.

Our other main concern was our difficulty curve. We didn’t want to just remove the last 20 levels from the game because the overall difficulty would be drastically reduced; older players could find the game far too simple. But, we also acknowledged that each of the new mechanics had to be introduced and scaffolded over a few levels to ensure players understood the underlying concepts; we couldn’t just use the levels with the coolest mechanics. To keep our difficulty curve the same, we decided to rearrange some of our levels and create a few new levels to fill gaps created by introducing concepts sooner.

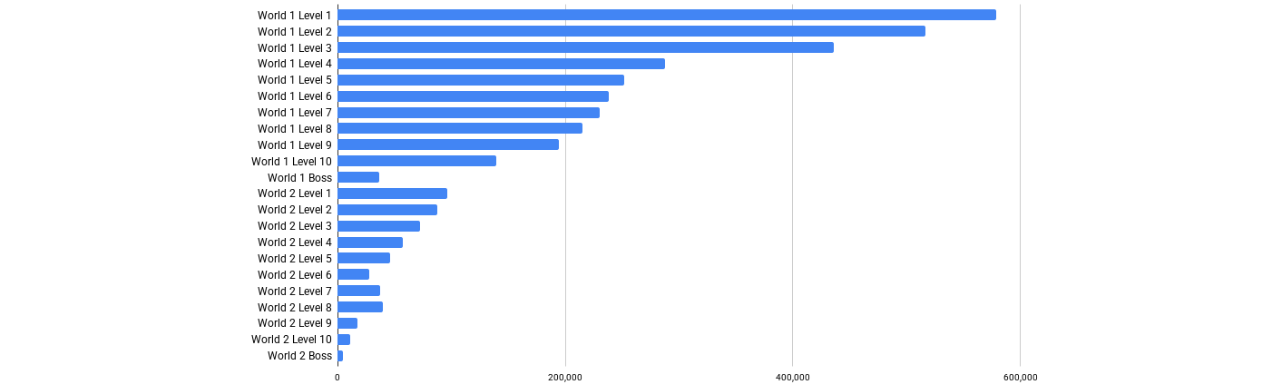

Our difficulty curve, showing how many players completed each level. The more players complete the level, the easier the level is. This isn’t a perfect measurement, but works well enough to be great for level design feedback.

With about 6 months of player data we were able to see that our level editing was working well. The first 15 regular levels are perfectly in order for rate of completion and depicted a nice difficulty curve. The only major break from this visualization is the first boss battle which has about half of the rates of completion when compared to the level that came before, and the one that came after. And, yes, the first boss level is more difficult than all of the levels in its world, and even a few from world two, but it’s perfect for a challenge players are meant to strive for. According to our data, the second boss level is the hardest level of them all, which again makes sense because players wouldn’t be able to unlock that level unless they’ve beaten all the other levels (and we wouldn’t want it to be a disappointment).

We used a lot of preproduction work to design the core concept of Push Pull Puzzles, and a fair amount of data guided editing for the PBS Kids release of the game. Push Pull Puzzles still ranks in the top 10 most popular games on PBS kids, and has had over 2 million plays since its release in 2020. A bottom up design allowed us to focus on the physics puzzles being fun, and player analytics helped us to polish those levels for a mass market.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack