Directing Players with Keys

When designing open-world or non-linear videogames, you’ll want to control the player’s progression and flow to some degree. The last thing any designer wants is for a player to be ill-equipped and reach a state in the game that’s unbeatable. Or worse, so frustrating that they’ll never play again. So, what do you do? Lock it!

Lots of games make entire areas inaccessible so players can’t progress until they hit the progression level the designer intends first. Many games even lock the areas literally, requiring the player to find the key. The key is often found in a location that increases the player’s power or progresses the story. Often, a boss will guard these keys and players are rewarded for beating them not only with the key but with new weapons, player actions, or experience, making them ready to take on the new area. Not all games are as straight forward as that though, and there’s a lot of ways to hide a key.

Kinds of Keys

Some games have literal keys. If you’re making a game in an urban environment, having literal locked doors and keys works. If you’re in a military or science facility, changing a regular metal key to a keycard makes sense. But sometimes your game’s theme doesn’t have a key equivalent, that’s when you need to be a bit more sneaky.

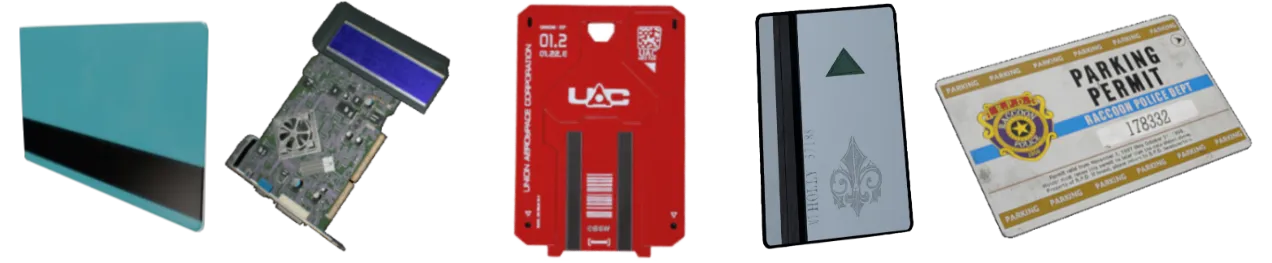

If your game has social elements or if you want your players to feel like they’re interacting with people, you can turn the characters into keys. Make the players do them favors like bringing them an item, commonly known as a “fetch quest”, or hit a certain relationship level with them by bringing them gifts and interacting with them over time. When they complete the task, the character can literally open a new area for the player, or they can give the player access to information used to progress.

In Metroidvanias this key system often takes the form of unlocking a new ability that allows you to get to new locations. For example in Legend of Zelda games Link usually does get real keys in a dungeon to unlock doors, but he also gets a mystical item that is required to progress and beat the boss.

Think carefully about which option you choose and how you implement it. It can have quite an impact on your game. Don’t get too repetitive - The worst thing you can do with a key system is to make the player AWARE that it’s a key system. Not only do you break immersion, you make the player start thinking about the task at a meta level, which quickly becomes just another checklist.

Metroid: The Good and The Bad

Metroid implemented key systems in two ways. One that makes the game better, and one that makes the game (seemingly) worse.

In Metroid, Super Metroid, and Metroid Prime, the player gets stronger over the course of the game by upgrading Samsus’ weapons and abilities with new tech. These weapons then allow the player to revisit previous locations and interact with them in new ways, allowing them to proceed. For example, Samus is unable to reach some areas of the map because there are rocks or debris that are blocking her way. When she gets her missiles she is allowed to proceed, because the player now has the ability to blow up the rocks.

This method works for these games because it leans into the game’s objective, making the player feel like an awesome, powerful, and clever bounty hunter. Mechanically, this type of key serves multiple purposes, giving the player the ability to interact with the world in a new way. It doesn’t feel like the key was just a hindrance for the sole purpose of holding them back.

Alternatively… let’s talk about Metroid: Other M. In Other M, instead of upgrading your abilities and powers through the game via exploration and discovery, you are instead given “clearance” to use your abilities at key points in time.

Samus getting ordered around.

Mechanically, this is the same as the last implementation, BUT it robs the player of the feeling that they were the ones increasing their powers and abilities. This system implies that they had all of the upgrades all along but would not use those upgrades (even in situations where it was life or death) unless they were instructed to do so by a superior officer. The dissonance here between lone wolf bounty hunter and soldier following strict orders is so severe that most players see Other M as one of the worst Metroid games even though Team Ninja’s combat did have some great moments (the dramatic cutscenes also didn’t help).

To be fair, Other M’s approach was trying to shake up the formula in a way that still kept the core mechanics intact. There are only so many sequels you can make to a game that follow the same blueprint before it starts to feel repetitive and overshadows its polish. The approach Other M took did not work with the power fantasy or with the player’s vision of who Samus (a notoriously silent protagonist) was, but it arguably respected her history more than some other games by acknowledging that she had those power-ups rather than having to refind them.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack