Your Players Can't Count

Players can’t count. Players also can’t read. And Players can’t listen.

At least not in the way game designers assume they can. These aren’t criticisms. They are just basic limits of human cognition that come up all the time when people play games.

Before we were Videogame Workshop, we worked at PBS where we made a lot of games for kids. After watching thousands of play sessions, we started to notice patterns. The things kids struggled with were almost always the same things adults struggled with. When a mechanic broke down or a player got confused, it usually wasn’t because the design was too complex. It was because the human brain does not do certain tasks very well under pressure and we were dealing with some sort of cognitive overload with everything being new.

So we started to think of these limitations not as player weaknesses but as design constraints. If we can reduce the cognitive load around counting, reading, and listening, players have more mental energy for the interesting parts of our games. The strategy. The problem solving. The thinking.

Players Can’t Count

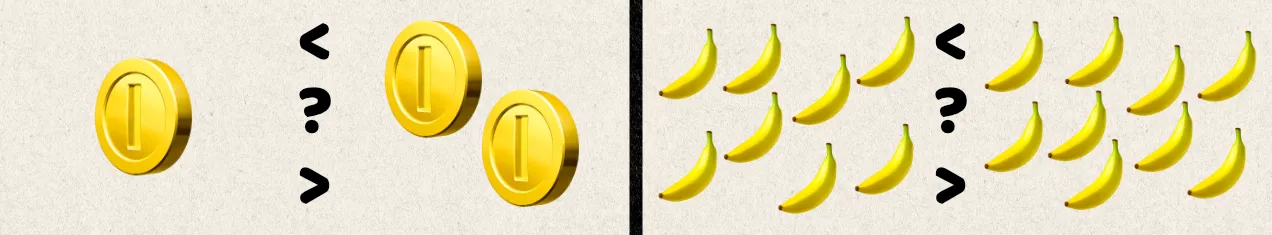

If you flash two groups of objects on a screen for a very short time, people can tell the difference between one, two, and three. But once you go past that, accuracy drops fast. And players really struggle when the quantities are close together.

There is a biological reason for this having to do with the way we process stimulus. Visually, humans are naturally better at noticing when one group is about double the size of another. You can see this in young children who have not learned formal math. You can also see it in adults who did not grow up with formal math education. If you ask, “What is halfway between one and nine?” a surprising number of people say “three.” That sounds wrong on a number line, but it makes perfect sense on a logarithmic scale where you think one, two, four, eight. Three is nice because it has three consecutive numbers that are easily comparable against each other 1, 2, 3. Especially int he early game this helps new players process the game’s information quicker so they can focus on new mechanics.

After this, you’ll probably start seeing three everywhere. Zelda, for example, starts you with three hearts. When players lose hearts, they don’t really count how many they have left, they just get a feel for how dangerous the situation is. They go from full to two, from two to one, from one to flashing red. Big perceptual changes. Heart containers scale in a simple way that avoids small-number comparisons.

Same goes for health bars in RPGs. Players rarely look at exact numbers unless they are in a very specific community like competitive Pokémon (shout out showdown). Most people see a bar as full, half, a quarter, or almost gone. They are tracking chunks, not numbers.

Collectibles work the same way. In Donkey Kong Country you don’t process picking up exactly five bananas. You grab a banana bunch and let the system total it up. The number doesn’t really matter until you hit 100 anyway. It communicates “many” without requiring you to count anything at all.

So when we say “players can’t count,” we don’t mean they can’t do kindergarten math. We mean humans are bad at comparing quantities quickly, and games require those comparisons constantly. Good design uses this knowledge to help players grasp information instantly instead of forcing them to calculate.

Players Can’t Read

Players are not calmly absorbing every letter. They are skimming and guessing and filling in blanks using pattern recognition. But this is true for all reading. Our brains are really good at pattern matching and we use things like structure to infer things rather than reading every letter or every word.

There is a common demonstration where you mix up the letters inside a word but keep the first and last letter the same. Most people can still read the sentence with almost no difficulty. That is because some reading is based on shape and expectation. We use heuristics to process the information quickly. But, when our expectations are subverted, like if the usual shape of a word is broken, like alternating upper and lowercase text, it becomes wAy HaRDeR tO pArSe.

In a game you have to assume players are reading under additional cognative load. They might be navigating enemies, tracking cooldowns, planning moves, or reacting to audiovisual feedback. Their attention is divided. They simply don’t have the mental bandwidth to carefully read even short instructions unless they are extremely clear. So, maybe use that to your advantage.

This is why familiar symbols and tropes are powerful. Hearts means health. A green arrow means go. Red means danger. Card suits communicate poker hands without requiring explanation. These existing patterns do some of the cognitive work for the player. Games that lean into existing knowledge create smoother experiences. Games that fight what the brain expects create friction and confusion.

So when we say “players can’t read,” we mean that fast, accurate text parsing is not happening. Designers should assume players are skimming and should make everything as visually meaningful as possible.

Players Can’t Listen

Listening is even harder than reading.

The Stroop Test is a classic example of cognitive interference that you can try right now. In the test, participants are told to say the color of a word instead of reading the word itself. It is simple, but the moment your brain sees the text “BLUE” written in red ink, your automatic reading reflex interferes. You need to maintain the instruction, filter out a distraction, and perform the task repeatedly. That’s actually asking a lot for something that sounds trivial.

Short-term memory only lasts twenty to thirty seconds. Working memory can hold about 6 - 7 items. That’s not much, and games often ask for far more. Meanwhile the player is also watching enemies, tracking health, thinking about controls, and reacting to feedback.

Players often forget instructions not because they are ignoring them but because other things push those instructions out of memory. If you give a tutorial step too early, the player will forget it by the time they need it. If you deliver instructions while something exciting happens on screen, the player will miss them entirely.

You can design around this. Reduce distractions. Present information only when it is relevant. Give reminders at the right moment instead of the beginning. Gently reroute players when they do something incorrect instead of punishing them.

A good example is Into the Breach. If you try to move a mech to the wrong tile during the tutorial, the game does not give you a red error message. It simply highlights the undo button and shows you what to do instead. No negativity, no cognitive overload, just a gentle correction.

Players are going to press the wrong buttons. They are going to poke at the UI. They are going to try strange things. Sometimes the best thing to do is embrace the chaos. Hide small jokes or reactions in places players are likely to prod. It makes the game feel responsive instead of brittle.

So when we say “players can’t listen,” we mean that human working memory is extremely limited, and most instructions are forgotten unless they are presented right when they matter.

TLDR

Players cannot count quickly. They cannot read thoroughly. They cannot listen reliably. These are not shortcomings. They are researched limitations people bump up against. When we build games with these constraints in mind, our designs become clearer and more enjoyable. We remove cognitive friction and create more space for players to engage with the interesting parts of our games, the strategic and thoughtful parts. When you do that, the entire experience improves.

Consider becoming a patron for exclusive content and perks.

Or sign up for our substack